Quoted string parser State Diagram

A (Finite-) State Machine is a method of determining output by reading input and switching the state of the machine (computer program). Depending on the type of State Machine (more on this later), the state of the machine is changed by looking at the current state, sometimes in combination with looking at the input.

If you’re a web developer, you may (in a dark past) have seen something like this:

if (logged_in()) {

if ($action == "logout") {

act_logout();

} else {

# Show a form with a logout button

display_logout();

}

} else {

if ($username != NULL && $password != NULL) {

act_login();

} else {

display_login();

}

}This could be seen as a State Machine, albeit a crude one. It has two states: You are either logged in, or logged out. Depending on the current state and the input ($action), the machine switches between these two states, or remains in the same state and displays information.

The example above would not normally be called a State Machine, especially since the example works over HTTP, which is a stateless protocol. However, it does explain the theory of State Machines rather well. Later on, we’ll look at some of that theory, and more formal State Machine implementations. Let’s first look at what State Machines are useful for.

State Machines are a rather abstract concept if you’re not used to dealing with them. They have their roots in mathematics (where we also find Non-Finite State Machines, but we won’t be going into those here).

So what are State Machines used for? In the programming world, generally speaking, State Machines are useful when you read input and what you have to do with that input depends on things previously encountered in the input.

In practice, State Machines are often used for:

State Machines exhibit some basic properties. Not every type of State Machine has all of them, but they always have at least one of them:

lightswitch=on, heatsensor=off, etc.There are two types or Finite-State Machines which are typically used in computer programs:

The Acceptors/Recognisers read bits of input and in the end tell you only if the input was accepted or not. One example would be a State Machine that scans a string to see if it has the right syntax. Dutch ZIP codes for instance are formatted as “1234 AB”. The first part may only contain numbers, the second only letters. A State Machine could be written that keeps track of whether it’s in the NUMBER state or in the LETTER state and if it encounters wrong input, reject it.

Transducers on the other hand continuously read pieces of input and for each piece of input produce either some output or nothing. What it produces can depend on the input and the current state of the machine.

A good example of this is a string parser that allows the user to enclose a part of the string in quotes so that it is treated as a single item. On the Unix shell this is used to refer to file names with a space in them.

The State Machine reads one character at a time. When a space is read, it assumes a new element is starting. If it encounters a quote, it enters the QUOTED state. Any characters read while in the QUOTED state are assumed to be part of the same element. When another quote is encountered, the State Machine transitions to the UNQUOTED state.

Let’s look at a simple example of an acceptor, using the above mentioned Dutch ZIP code example.

#!/usr/bin/python

import string

STATE_NUMERIC = 1

STATE_ALPHA = 2

CHAR_SPACE = " "

def validate_zipcode(s):

cur_state = STATE_NUMERIC

for char in s:

if cur_state == STATE_NUMERIC:

if char == CHAR_SPACE:

cur_state = STATE_ALPHA

elif char not in string.digits:

return False

elif cur_state == STATE_ALPHA:

if char not in string.letters:

return False

return True

zipcodes = [

"3900 AB",

"45D6 9A",

]

for zipcode in zipcodes:

print zipcode, validate_zipcode(zipcode)This acceptor state machine has two states: numeric and alpha. The state machine starts in the numeric state, and starts reading the characters of the string to check. If invalid characters are encountered during any of the states, the function returns with a False value, rejecting the input as invalid.

In this example we do not check the maximum allowed length of the two parts of the ZIP code. The example is merely to demonstrate a potential Acceptor State Machine. This problem would obviously be better solved with a regular expression (which incidentally are usually implemented using State Machines).

Let’s look at an example of a simple transducer state machine. I’ve already mentioned the quote example, so here it is in the flesh:

#!/usr/bin/python

s = "ls -la 'My Documents' /home /etc"

STATE_UNQUOTED = 1

STATE_QUOTED = 2

CHAR_QUOTE = "'"

CHAR_SPACE = " "

words = []

cur_state = STATE_UNQUOTED

cur_word = ''

# Break s up in words. Words are delimited by

# spaces, unless we're between quotes.

for char in s:

if cur_state == STATE_QUOTED:

if char == CHAR_QUOTE:

words.append(cur_word)

cur_word = ''

cur_state = STATE_UNQUOTED

else:

cur_word += char

elif cur_state == STATE_UNQUOTED:

if char == CHAR_QUOTE:

cur_state = STATE_QUOTED

elif char == CHAR_SPACE:

if cur_word:

words.append(cur_word)

cur_word = ''

else:

cur_word += char

words.append(cur_word)

print wordsThe output of the above State Machine is:

['ls', '-la', 'My Documents', '/home', '/etc']As you can see, “My Documents” has been successfully parsed as a single argument.

Let’s examine the State Machine up close.

There are two possible states: UNQUOTED and QUOTED. We start in the UNQUOTED state and then loop over each of the characters in the string. These characters are the input into our state machine, and thus are our symbols. If we’re currently in the UNQUOTED state, and the character we read is a quote, we transition to the QUOTED state. Otherwise, if the character is a space, we add the current to the list of words. This is an action. If the character is anything else, we append it to the current word (also an action)

If the State Machine is currently in the QUOTED state, we do basically the same thing as the UNQUOTED state, except that the space character is not treated as a word delimiter. Instead, it is just append to the current word. Encountering another quote while already in the QUOTED state means we’ve reached the end of the quoted word, so we append it to the list of words and transition back to the UNQUOTED state.

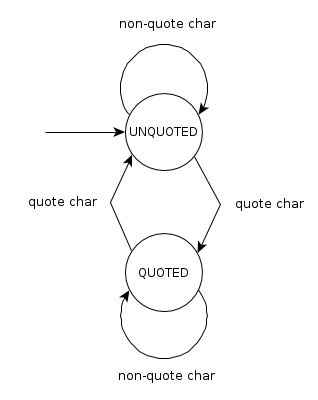

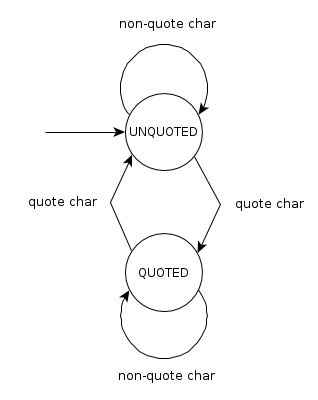

A State Diagram is a visual method of describing a State Machine. There are many varieties of State Diagrams, each with different rules. The basic form though can be seen in figure 1, which describes the state machine from the previous example.

Quoted string parser State Diagram

In this example diagram the start state (UNQUOTED) is indicated by the arrow coming out of nothing going into the UNQUOTED state. The “quote char” arrows are transition conditions. Whenever a quote character is encountered, the State Machine changes state. It is debatable whether we should include the “non-quote char” arrows, since they do not indicate a state transition. However, since we want to model all the input we can receive, we will include them.

This particular State Diagram does not model the action of adding words to the list when a white space occurs. This is because actions that are internal to a state are not modelled in classical State Diagrams. When modeling State Machines as implemented in computer programs, you may therefor want to make use of UML State Diagrams.

Our simple example above is a completely hand-written custom implementation of a State Machine. The state transitions and actions are all handled within the for loop. This can quickly become messy when we’re dealing with bigger state machines, so we want to create an Abstract State Machine handler. There are many ways to implement Abstract State Machines, and here is an example of one:

class TransducerError(Exception):

pass

class Transducer(object):

def __init__(self, input, start_state):

self.input = input

self.output = []

self.cur_state = start_state

def run(self):

for symbol in self.input:

method = getattr(self, 'state_%s' % (self.cur_state), None)

if not method:

raise TransducerError(

'No method handler found for state \'%s\'' % (self.cur_state)

)

method(symbol)

return(self.output)

def transition(self, new_state):

handler = getattr(self, 'action_%s_exit' % (self.cur_state), None)

if handler:

handler()

handler = getattr(self, 'action_transition', None)

if handler:

handler(self.cur_state, new_state)

handler = getattr(self, 'action_%s_enter' % (new_state), None)

if handler:

handler()

self.cur_state = new_stateThis Abstract State Machine makes use of Python’s powerful meta-programming capabilities to handle states and state transitions. The run() method reads tokens from the input. For each token it determines the current state the state machine is in and tries to find a method called state_CURRENT_STATE on the current object instance. We can then extend the Transducer class and define methods for each different state.

When we transition into a different state, the Transducer class automatically tries to find entry, transition and exit methods.

The exit methods (for example: action_quoted_exit) are called when we exit that particular state.

The action_transition method, if found, will be called whenever we transition state, regardless of the state we came from and are going to. It is called with the previous and the new state as parameters.

Finally, the entry action (for example: action_quoted_enter) is called when we transition to that particular state.

Here’s how we would implement our string parser example using the abstract Transducer State Machine class.

s = "ls -la 'My Documents' /home /etc"

CHAR_QUOTE = "'"

CHAR_SPACE = " "

class Splitwords(Transducer):

def __init__(self, s):

Transducer.__init__(self, s, 'unquoted')

self.output.append('')

def state_unquoted(self, c):

if c == CHAR_QUOTE:

self.transition('quoted')

elif c == CHAR_SPACE:

self.append_word()

else:

self.append_char(c)

def state_quoted(self, c):

if c == CHAR_QUOTE:

self.transition('unquoted')

else:

self.append_char(c)

def append_word(self):

if self.output[-1]:

self.output.append('')

def append_char(self, c):

self.output[-1] += c

sw = Splitwords(s)

print sw.run()The output:

['ls', '-la', 'My Documents', '/home', '/etc']You can get the full example to try it out.

As you can see, the abstracted implementation of the State Machine is much clearer. The current state is automatically handled by calling the correct methods. Actions and state transitions are clearly visible in each state.

Here’s another example which shows how you can parse structured statements. In this case, we parse an SQL statement.

s = "SELECT a, b FROM table WHERE a > 5 ORDER BY b"

class SQL(Transducer):

def __init__(self, s):

Transducer.__init__(self, s, 'select')

self.output = {

'select': [],

'from': [],

'where': [],

'order': [],

}

def state_select(self, token):

if token == "FROM":

self.transition('from')

elif token == "SELECT":

pass

else:

self.output['select'].append(token)

def state_from(self, token):

if token == "ORDER":

self.transition('order')

elif token == "WHERE":

self.transition('where')

else:

self.output['from'].append(token)

def state_where(self, token):

if token == "ORDER":

self.transition('order')

else:

self.output['where'].append(token)

def state_order(self, token):

if token == 'BY':

pass

else:

self.output['order'].append(token)

sw = SQL(s.split())

print sw.run()This example produces the following output:

{'where': ['a', '>', '5'], 'from': ['table'], 'order': ['b'], 'select': ['a,', 'b']}Of course this example is far from complete. It lacks proper syntax checking, is case-sensitive and doesn’t properly sanitize various values. It demonstrates how one could create a very clear parser for structured statements. In the real world, the program would have access to which fields and tables are available, which can be used to check the parameters to the various SQL elements.

As we’ve discovered, State Machines are a powerful method of programming context-sensitive input-handling routines. While it is if often possible to write such routines in different ways, State Machines provide a simple, elegant, easy to extend and clear method of implementing such routines. They have a wide variety of uses, from simple input validators to full-blown parsers.

We can mix and match both Acceptors and Transducers, we can chain multiple State Machines to each other and we can easily model their behaviour using diagrams.

Abstract implementations of State Machines are available for many, if not all, programming languages, ranging from simple implementations to completely extendable toolkits complete with graphical design software.

Copyright (c) 2011-2019, Ferry Boender

This document may be freely distributed, in part or as a whole, on any medium,

without the prior authorization of the author, provided that this Copyright

notice remains intact, and there will be no obstruction as to the further

distribution of this document. You may not ask a fee for the contents of this

document, though a fee to compensate for the distribution of this document is

permitted.

Modifications to this document are permitted, provided that the modified

document is distributed under the same license as the original document and no

copyright notices are removed from this document. All contents written by an

author stays copyrighted by that author.

Failure to comply to one or all of the terms of this license automatically

revokes your rights granted by this license

All brand and product names mentioned in this document are trademarks or

registered trademarks of their respective holders.